Polk’s 50th Anniversary: College’s Five Decades of Growth Began with Pughsville

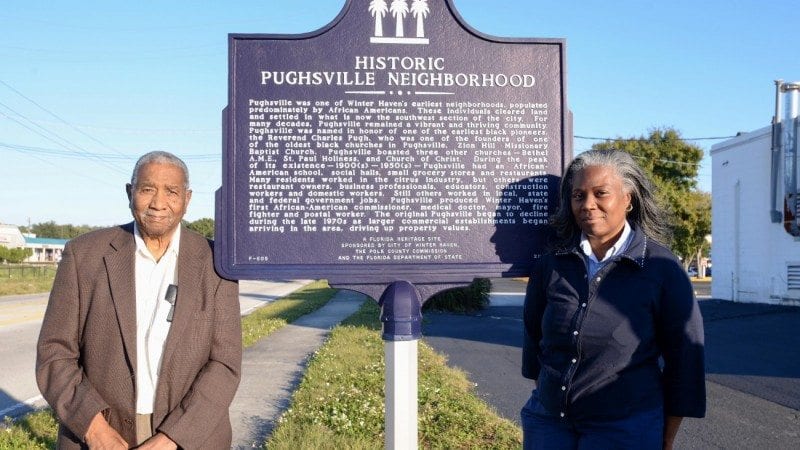

Lemuel Geathers and Patricia Smith-Fields, natives of Pughsville, stand near a historical marker for their neighborhood. The rezoning of Pughsville in the 1960s helped bring Polk State to Winter Haven.

For 50 years, the story of Pughsville and its contributions — rather sacrifices — in the name of affordable, accessible higher education has gone largely untold.

That changes now, in the midst of Polk State’s 50th anniversary year, because no recognition of the College’s history would be complete without also recognizing Pughsville.

“Someone needs to know about this, and the people who know the story, they’re dying really quick,” said Lemuel Geathers.

Geathers, 89, is a Pughsville native. He was born in a small house right next door to the home where he and his wife, Juanita, raised six children and still live today. A longtime educator, Geathers was the first African-American to be elected to the Winter Haven City Commission and to serve as mayor.

Geathers was also part of the process to rezone Pughsville, allowing for Polk State College to come to Winter Haven.

“The African-American community wanted opportunities just like everyone else,” Geathers said. “It was a big thing to have a college come to town.”

Bringing Polk State to Winter Haven

In 1964 Polk State, then Polk Junior College, set up shop inside the Bartow Air Base. The location was always intended as temporary, but when 1,200 students showed up on the first day of classes — more than twice the number expected — the College almost immediately started scouting locations for a permanent campus.

The City of Winter Haven wanted the campus, and it was willing to give the College its nearly 100-acre golf course to make it happen. The problem was that the city was legally obligated to replace the golf course — and that meant it needed money.

The proposed solution was to rezone Pughsville from residential to commercial, making way for fast-food restaurants and big-box stores. The city would expand its tax base and be able to create another public golf course. Pughsville properties would command higher prices than they would have under the previous zoning designation.

But it also, effectively, meant a community would cease to exist.

City officials met with residents to make their case. There were meetings in local churches. Geathers recalls going door to door on behalf of the cause. The residents heard the proposal. They considered the pros and mulled the cons. In the end, they agreed to rezone and, in many cases, move on.

“Any college town is a good place to live,” Geathers said. “Education brings good things to a community. Education brings out the truth. It brings jobs.”

Added Juanita Geathers: “Having the College here was going to help the total community, not just Pughsville, to have better lives.”

From the rezoning to present day, the story goes like this: The College got its first campus on 100 acres of former golf-course land overlooking Lake Elbert. That campus grew and grew until the College expanded again, adding Polk State Lakeland and the Polk State Airside Center, then two locations in Lake Wales, and in 2014, the Polk State Clear Springs Advanced Technology Center in Bartow.

The overarching theme of the growth has been access — which was exactly the point back in the 1960s, Lemuel Geathers explained.

During the days of segregation, Pughsville children had to walk all the way to Florence Villa, past the white schools, to attend school on the northern edge of Winter Haven. Those who made it to college had to leave the county altogether, to attend Bethune-Cookman or Florida A&M University.

“Because of Polk, I’ve seen people go to college who probably wouldn’t have had any other opportunity,” Geathers said.

Added Robert Atkins, vice president of the Historic Pughsville Association Inc.:

“We felt Polk State was a stepping stone. It was going to give the black people a chance to catch up and transfer to UF or FSU or the University of Miami. That was the interest in the College,” he said.

The Pughsville That Was

Many people have probably never heard of Pughsville, but it is, as they say, just a stone’s throw from Polk State Winter Haven. Primary boundaries of the area include Avenue O Southwest south to Cypress Gardens Boulevard, and 5th Street Southwest east to 3rd Street Southeast. A Big Lots store and car dealership now sit at what was once the heart of Pughsville.

As Geathers tells it, downtown Winter Haven was once the predominantly African-American section of town. When developers started snatching up properties at the turn of the 20th century, African-Americans moved either north to Florence Villa or south to Pughsville.

To hear residents’ memories, Pughsville, named for early settler the Rev. Charles Pugh, was an almost idyllic place to grow up. Residents provided for their families as maids and house painters, citrus workers and shoe shiners. In the evening, with the day’s work done, kids played marbles and stickball in the streets. Every weekend, there was a community fish fry.

“It was a very close-knit community. You could leave your doors open and feel safe that no one would come in. Everybody went to church. Everybody got along with everybody,” said Russell Burney, president of the Historic Pughsville Association.

Pughsville was a place where people took pride in what they had, because many of them had never had so much.

Patricia Smith-Fields remembers how her grandmother, Lucressie Smith, always made sure her Pughsville home was trim and tidy. The house stood on Avenue Q Southwest, within sight of where a Taco Bell stands today.

The wood-frame, two-bedroom, white-with-pink-trim house was a gift to Smith, a widower who cleaned houses to support four children. After their father died, Smith’s brother used their inheritance to buy the property and make her a homeowner.

“Back then, the majority of African-Americans rented,” Smith-Fields said. “Homeownership was something significant. That house was her prized possession.”

A few years after the rezoning, as many of the neighboring houses had been abandoned or torn down for commercial development, Smith had to leave her house, too. Her health was failing, and living on her own was increasingly difficult.

“Even then, she talked about wanting to be in her house,” Smith-Fields said. “We would take her there and let her tinker around, just to lift her spirits.”

Smith died in 1977. Smith-Fields lived in the home for a few years before the family sold it in the 1980s.

“It was a sense of loss,” Smith-Fields said. “Pughsville was a place for friends and community. There was a sense of kinship. That all demised with the rezoning.

“But I’ve never detected any bitterness. We wanted to help with progress. We wanted to give up our community to help with that progress.”

Enduring Partnership

While Pughsville’s role in the growth of Polk State has received only passing attention in the past half-century, it has never been forgotten.

The College is a longtime sponsor of the Historic Pughsville Association’s annual festival, and about three years ago, the Polk State College Foundation established the Historic Pughsville Association, Inc. Scholarship, which is awarded annually to a current or past president of Pughsville, or a descendant or relative of the community.

“At Polk, we often say that we ‘stand on the shoulders of giants.’ That adage certainly applies to Pughsville,” said Polk State President Eileen Holden.

“Without Pughsville, the course of history for this institution, if not for the entire city, might have been dramatically different. The Pughsville residents were giants in their foresight and their willingness to organize behind a common goal. The College, and the generations of students who have studied here, are forever grateful.”